Blog

Finishing Tracks: 7 Ways to Turn an Eight-Bar Loop into a Full Arrangement

23 Oct '2019

It’s a situation almost every producer has been in – you spend so long crafting the perfect beats, sketching a dirty bassline, programming a kick-ass synth patch, and getting the vocal just right… but then where do you go from there?

With all the samples in the world at your disposal, especially thanks to easy browsing in Loopcloud, it’s easy to spend all your effort on perfecting an eight-bar or sixteen-bar loop, only to get paralyzed when trying to spin it out into a whole track with its own arrangement.

In this article, we’ll give you some strategies for getting yourself out of the loop and back into the track-making mindset.

1. Subtractive Arrangement

You’ve got to the stage where your eight-bar loop sounds boss AF, but you can’t just play it 20 times to an audience and get away with it. Here’s one way to quickly flesh out your clip into a full track.

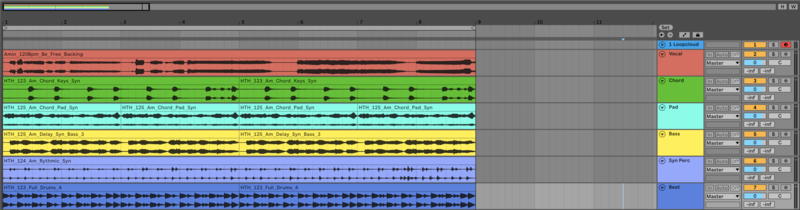

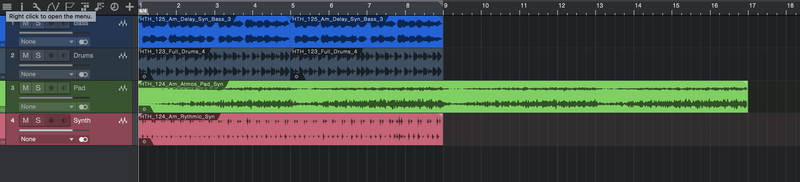

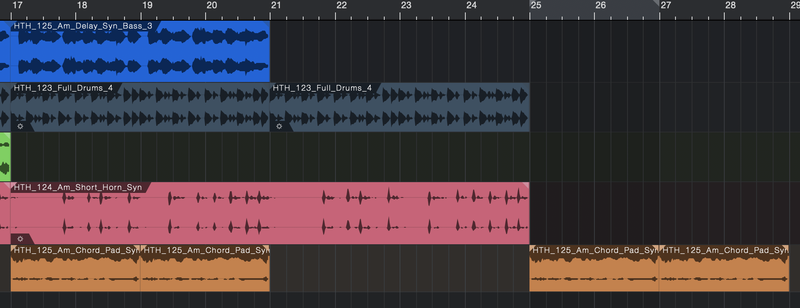

Start by zooming out on your timeline, and duplicating your existing loop right out through the duration of the tune you’re after – let’s say four minutes, which is 120 bars. Here we’re using the Loopmasters Hybrid Tech & House pack, after browsing for samples that go together on Loopcloud.

Now that you’ve got what is effectively an entire track of the repeated loop, it’s time to start sculpting it – literally taking things away from certain tracks to create the narrative of the entire song.

In our example below, we’ve started with beats and bass for the first eight bars, brought in the pad sound for the next eight, and then introduced our percussion and chords alternately for the next sixteen bars, taking the bass out for the last four of those. After this, our ‘main loop’ plays for 16 bars with all the elements working together, only working now as the climax to a group of elements that had been teased beforehand.

There are similar combinations throughout the rest of the track from there, and each movement tells the story in its own way.

Here’s the thing with subtractive arrangement: your track will still be quite dull, repeating the same elements over and over again, but by bringing in a context – removing and reintroducing elements – it’ll be much easier to see what needs to be done.

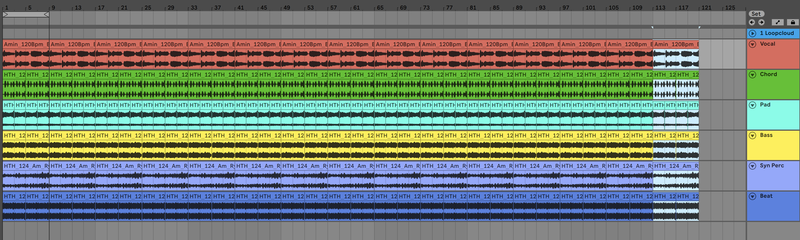

Below, we’ve started to add in transitional elements like risers and automated filters and started to edit and replace certain samples within the tune to move things forward and keep things interesting at the same time.

2. Never Close the Loop

One great way to get out of the eight-bar prison? Never send yourself down in the first place. That must be harder than it sounds, right? Well here’s the strategy that should get you there…

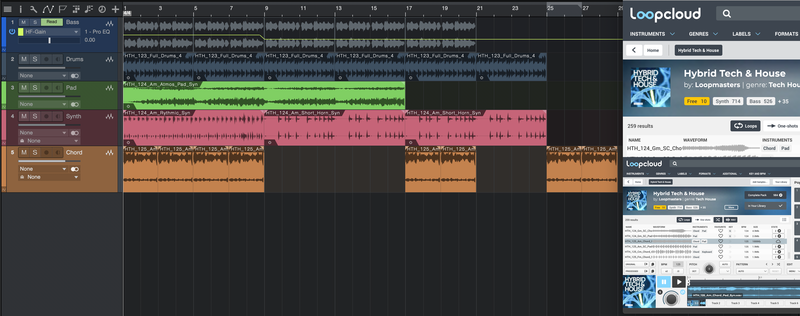

When you first start building your masterpiece, put your elements into place as usual, but when placing certain elements, either leave a gap or extend them further out past the loop. In the example below, our Pad sound lasts a full sixteen bars, while the other elements we’ve placed so far only last for eight.

The next step is to continue placing our elements into the 16th bar and beyond, but this time making variations. As you can see below, from bar 9, we’ve chosen a new synth sound, kept the drums the same, and filtered the bass, using the pad that had previously extended out to bar 17 as a scaffold to add elements.

We’ve also added a Chord track in, thickening the first eight bars, returning from 17 to 21, and then again in the ‘blank space’ between bars 25 and 29. This will now help us introduce a change from bar 25, hinging around that exact chord sound.

Never closing the loop means you’ll avoid the paralysis of listening to it over and over again.

3. Turn Chords into Arpeggios

One incredibly simple way to promote a bit of flavour throughout a track is to take an element that had once played multiple notes as a chord, and instead use it to play a sequence of those same notes as an arpeggio.

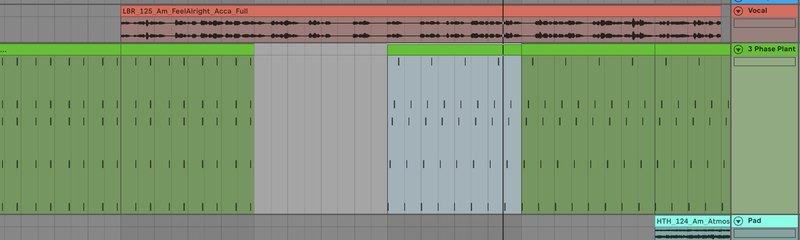

In the image below, we move from a straight chord stab, taking the same notes and only changing their timing to create an ascending arpeggio out of the original chord.

If you’re using samples, recreating the sound as close as possible using a synth is also a great way to change up the flavour of the sound and provide an interesting route for the track to go – see Switch Up Your Synth later in this article for more.

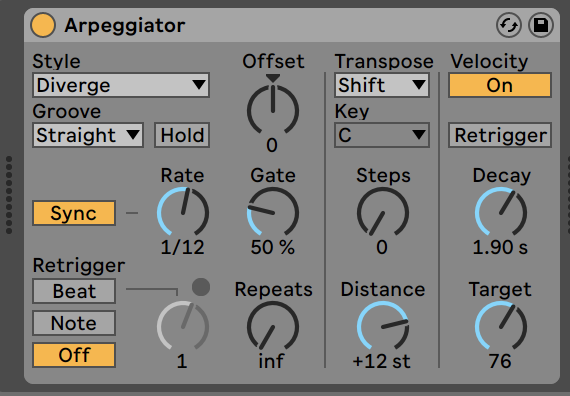

If you’re creating your instrument parts using MIDI, try using your DAW’s MIDI plugin functions to transform chords into sequences of notes.

Arpeggios don’t have to mean patterns that rise form a chord’s lowest note to its highest. Try creating descending. Or, for even more control check out how to turn your arpeggiator to MIDI in Ableton for ultimate flexibility.

4. Change Key

Keeping music interesting can be simple when you know what to do, but with music theory being a tough nut to crack, it helps to have some tools you can rely on. Case in point, how can you add a key change to your song or loop?

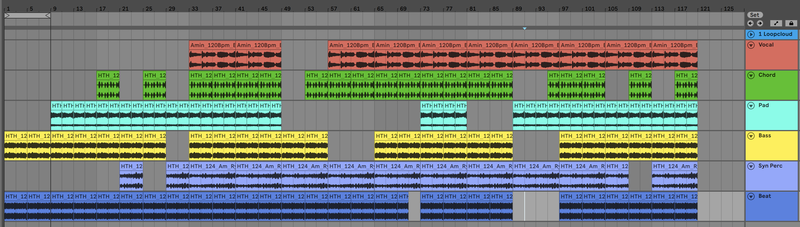

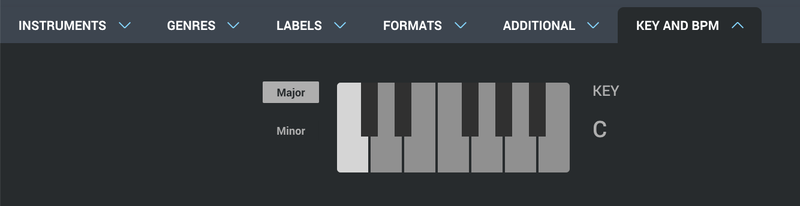

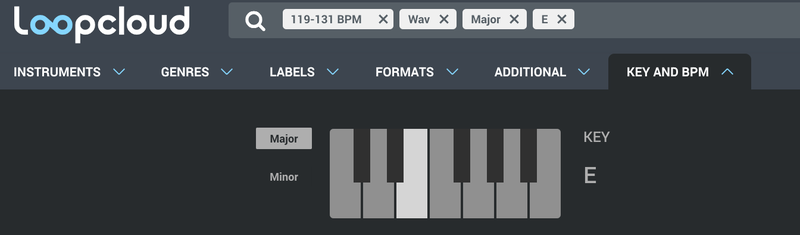

With Loopcloud, things get a little easier, as you can search by musical key, and many of our samples are named with the key in mind as well. The below example track is made up of samples that are all in A minor, and so the whole track is in A minor.

It’s easy to search Loopcloud for A minor samples to go with this tune – that’s how we made it, after all – but what key should you be searching out if you want to change key?

Your first port of call for a key change could be looking for samples in the relative minor or relative major of the key you’re in to begin with. Our A minor key shares all its notes with C major, and the way to determine that is because C is three semitones up from A.

If we were in F# major, samples in D# minor would also work with our track – again, the two are separated by three semitones.

How about trying to change the key to the dominant key? That’s seven semitones up, so from out A minor original position, we could then select samples in E minor, seven semitones up, to make a pleasant key change. Another example: if the original material is in D major, a nice key change would be to go to A major, seven semitones higher.

Finally, samples in the key two semitones higher than your current one can lead to a nice key change as well. From A minor, try going to B minor; if you started in F major, you’d head to G major and see how the transition works.

5. Switch up your Synth

Here’s one of the easiest ways to catch inspiration for a new development of the same material: if you’re using a synth or another MIDI instrument to generate one part of your track, simply duplicate the track and replace the synth. From here, it’s a simple (and inspiring) matter of scanning through presets until you find something that uses the same notes but sounds like it’s both fresh and a natural extension of the original synth line.

In the image above, we’ve started with a few bars of LennarDigital’s Sylenth1 synth, then in the next lot of bars have let NI’s Massive X take over the line, loaded onto another track but playing the exact same MIDI.

Thanks to some judicious patch selection, we’ve managed to get a similar sound, but the effect it has on the track (and the loop) as a whole is a nice way to spin the track out. Next, whenever we change the MIDI that we’re piping into Sylenth1, we can also try it out in Massive X for even more variation in our track.

6. Practise with Old Material

If you’re struggling to get out of the eight-bar loop zone, you’re not alone. You’ve probably been a this for a long time, building up your own untreasured stockpile of great ideas that never made it into tracks. So why not use them as practise runs? After all, by practising your abilities to get something from nothing will help you to Finish Tracks Faster.

"By forcing yourself to craft an intro, an outro, a variation on the main loop and fine some musical sprinkles to shake over the whole experience, you’ll get that vital practise and experience that’ll help you to turn your next good idea into a great whole tune."

Take something that never made it, and decide that it’s done for – this track idea is no more, it’s an ex track. Once you’ve committed to that, it’s time to turn it into a full arrangement anyway. You might not be nodding your head to every beat, but by forcing yourself to craft an intro, an outro, a variation on the main loop and fine some musical sprinkles to shake over the whole experience, you’ll get that vital practise and experience that’ll help you to turn your next good idea into a great whole tune.

You never know, the work you do to spin out a dodgy track and put it into a new context could result in you having a piece of music – or at least a section – that you’re very proud of.

7. Sample Yourself

Another way to use those old loops is as inspiration generators in their own right. Take a leaf out of the book of hip hop, export the loop and a couple of variations, and use that as an element in a completely different track.

By pitch shifting, retiming and twisting your bounce into a different context, you might find that it takes on a whole new character, perhaps serving a different purpose that you never imagined, and all that work you spent on the original will now count towards your current new track.

What’s more, if you’re only taking elements you created from scratch, there’s nothing to worry about when it comes to copyright – your second best royalty-free sample generator can often be yourself. (The best is always Loopmasters.)

Access 3.5 million sounds with a free trial of Loopcloud